Digest 40. The effect of incentives on (un)ethical behavior

The Global Business Ethics Survey® released in 2021 and based on data collected worldwide in 2020, revealed interesting but also alarming trends. First, only 14% of individuals believe that they work for organizations with strong ethical culture. Second, even those who work for companies with high ethical standards, have felt increased pressure to compromise those standards (specifically, 29% of employees reported feeling such pressure). Furthermore, nearly 8 in 10 employees have reported the observed misconduct higher up and 61% experienced retaliation for doing so.

These figures paint a worrisome picture, and there is no doubt that organizations need to take actions to improve their ethical culture and promote ethical behaviors. So, organizations (and managers) may be tempted to use rewards to encourage such behaviors. But…

…what’s the effect of monetary incentives on (un)ethical behaviors?

This is the question that Park and colleagues (2022) tried to answer by reviewing the academic research on the effect of incentives on unethical behavior across the management, economics and psychology disciplines.

First, they defined “incentives” any form of return offered to a person for actions and behaviors that they would not have otherwise chosen. While this definition is very large, in practice, research mostly examined the use of monetary compensation offered for exhibiting a certain performance – not only an ethical one. Second, the authors conceptualized unethicality as (a) constituting the violation of group, organizational, or community norms; or (b) involving forms of nontrivial harm (psychological, social, physical or financial) to individuals, groups, or communities; or (c) involving actions that suggest a neglect of widely respected rights, obligations, and virtues.

The studies included in the review are not only experimental studies conducted in labs, but also field studies conducted in real contexts. In these cases, examples of unethical behaviors associated to incentives come from various fields: in the educational sector, the presence of incentives based on students’ outcomes may lead to test score manipulation; in the healthcare, incentives may influence the choice of protocols used in treating patients; in the for-profit sector, incentives may be associated with executives’ account manipulation or selling at an increased cost for the employer in the case of salespersons.

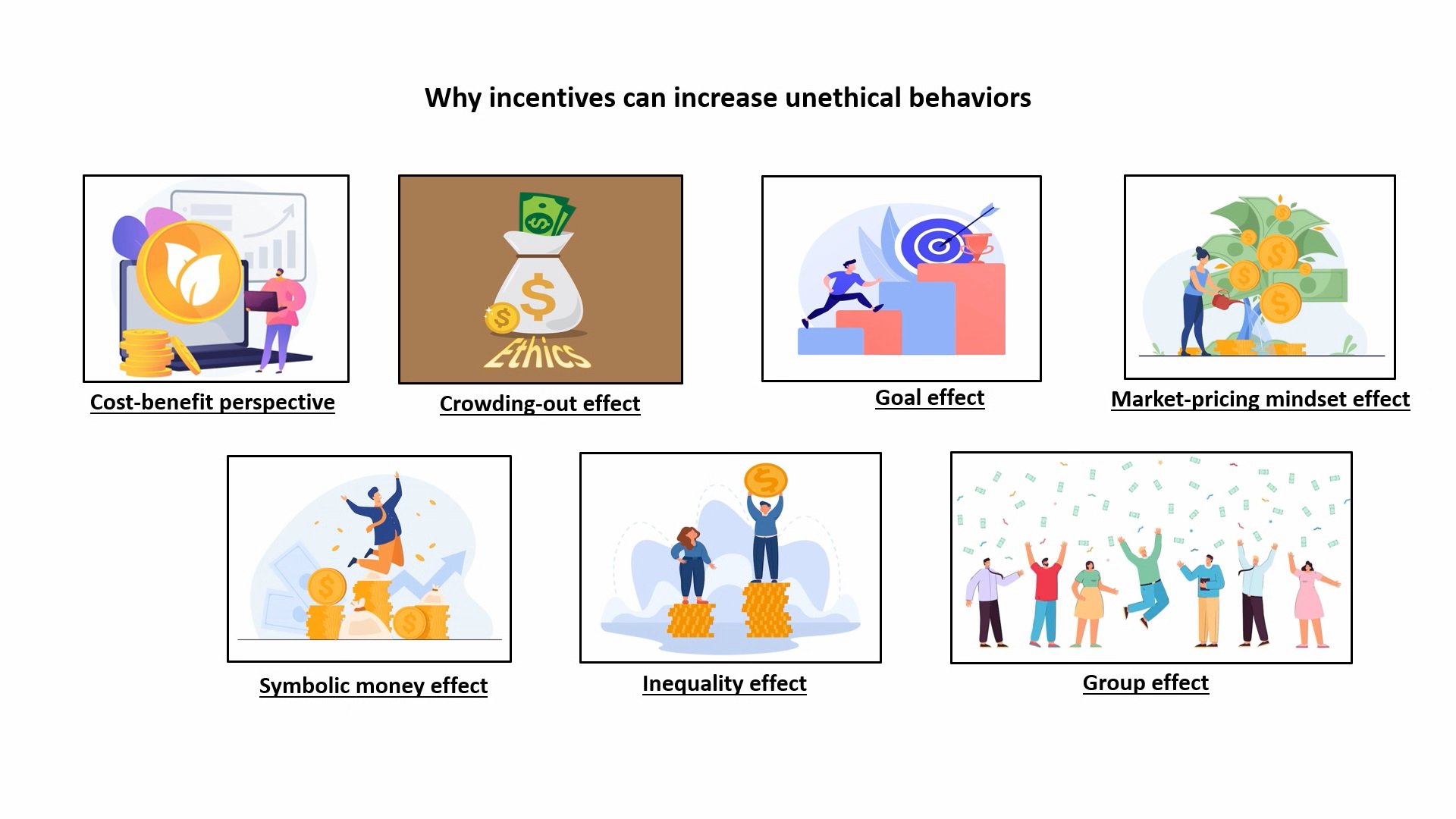

We “spoil” the conclusions of the study by revealing to our readers that ethicality might be negatively impacted by incentives. The most interesting part of the story is why that is the case. Seven theoretical perspectives can be adopted, each supported by empirical evidence.

The cost-benefit perspective. Acting unethically is considered the result of cost-benefit analysis. If unethical behavior appears to be bringing more benefits than costs – particularly to advance the person towards achieving the prospected reward, it is more likely to appear. This has been found when anonymity is guaranteed in dice-rolling games, or in call centers, if employees are told that the probability of having their calls monitored is nil. In these cases, then, the cost of cheating is nil too.

The crowding out effect. Acting ethically is considered as being intrinsically motivated, based on moral identity. Offering an incentive to act ethically may have the opposite, detrimental, consequence of reducing ethicality rather than increasing it, as if our brain could not accommodate both a moral and a material identity. Numerous experiments conducted both in economics and psychology provide ample supporting evidence for the crowding out effect. One study however found that with people with low moral identity, larger rewards actually increased the likelihood of ethical behavior.

The goal effect. This is based on abundant literature on goal setting, which finds that when working in a goal setting condition as opposed to a ‘do your best’ condition, participants are more likely to cross ethical lines, all the more so in the presence of financial incentives. One explanation of the goal effect is ‘resource depletion’, namely a state provoked by the pressure to achieve the goal that depletes individuals’ resources to act morally. Indeed, acting morally requires a substantial amount of energy (and so does the goal). The other explanation is termed ‘outcome bias’, that is the tendency to narrowly focus on the achievement of the outcomes specified by the goal ignoring everything else.

The market-pricing mindset effect. This perspective is very close to the cost benefit perspective with one important difference. Here, the idea is that some individuals hold a market-pricing mindset, and so they tend to consider all relationships and interactions under a utilitarian lens. Therefore, they do not specifically engage in a cost-benefit analysis, but they regularly tend to adopt a utility metric. This mindset is not a given trait but can be developed (i.e., increased or decreased). Research found that among individuals who are taught to (or induced to) think that making money is valuable, desirable and should be maximized, the likelihood that they will behave unethically is increased.

The symbolic money effect. People can value money not only instrumentally, but also due to its symbolic and emotional meaning (for example, it signifies that one is self-sufficient, independent, powerful, etc.). Although less supported empirically than other perspectives, this one also predicts that in the presence of incentives people act more unethically because money gives a sense of self-sufficiency that in turn reinforces one’s personal agency and reduces compassion and prosocial behaviors.

The inequality effect. Large pay differentials would trigger unethical behaviors via fostering the perception of being “relatively deprived” in those who are the least paid. Abundant evidence has been found, that the larger a potential pay increase or a bonus, the higher the likelihood that employees aiming for it will act unethically. Such behavior can consist, for instance, in misrepresenting accounts, or engaging in risky behavior. A qualified version of this perspective suggests that the inequality effect is stronger when perceptions of justice are low, which is supported by empirical evidence (see also Digest 37).

The group effect. Unethical behavior may be present in the context of group incentives, which is counterintuitive. This happens through two distinct mechanisms. The first mechanism is called the ‘group benefit’ effect or altruism-based unethicality. It was found that in the presence of a collective incentive, the likelihood of behaving unethically for the benefit of not just oneself but one’s work group can be higher than in the presence of an individual incentive. The second mechanism is called the ‘diffusion of responsibility effect’. This occurs when one’s sense of morality is altered by norms of unethical behaviors that can be observed among other team members sharing the same incentive.

The final contribution of this literature review is a dedicated section on field research in sectors where the incentive-ethicality link has been studied most, i.e., in the educational sector, in the health care sector, and in the for-profit sector (C-suites and sales). Typical unethical behavior found in the educational sector in the presence of incentives based on student outcomes, is test score manipulation. Incentives were also found to influence the choice of protocol used in treating patients in hospital with no obvious link to the patient’s need, as well as being more selective regarding the admission of a patient into a care unit. In the for-profit sector, higher incentives, or incentives framed as losses, tend to elicit more unethical behavior from executives, such as account manipulation, or such as selling at an increased cost for the employer in the case of salespersons.

Organizational implications

In light of the evidence presented in this review, organizational decision makers should bear in mind the following ideas.

First, rewarding ethical behavior is not a good idea, as it weakens the moral foundations of acting ethically, but may be a good idea when recipients’ moral identity is low.

Second, when in presence of incentives, providing employees with the knowledge that their behavior can be monitored, even if very rarely, is important in order to minimize unethical behavior.

Third, monitoring ethicality is even more crucial in the presence of group incentives that may create added peer pressure and/or encouragement to act unethically.

Fourth, very large incentives should be avoided if acting ethically is a central consideration.

Finally, justice perceptions are key in preventing unethicality at work. For how managers and supervisors can be perceived as fairer in performance evaluations that often underlie incentives, check out Digest 14 and Digest 33.

——

Reference: Park, T. Y., Park, S., & Barry, B. (2022). Incentive Effects on Ethics. Academy of Management Annals, 16(1), 297-333. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2020.0251