Digest 12. Performance management across borders: Mind the cultural differences

One of the biggest challenges that HR leaders of multinational companies face is how to define practices that are effective across countries and how to make the necessary adaptations to accommodate the different cultural values and needs.

Along these lines, a research by Chiang and Birtch (2010) intended to find out whether culture dimensions explain PM practices, its purposes and their variations across countries.

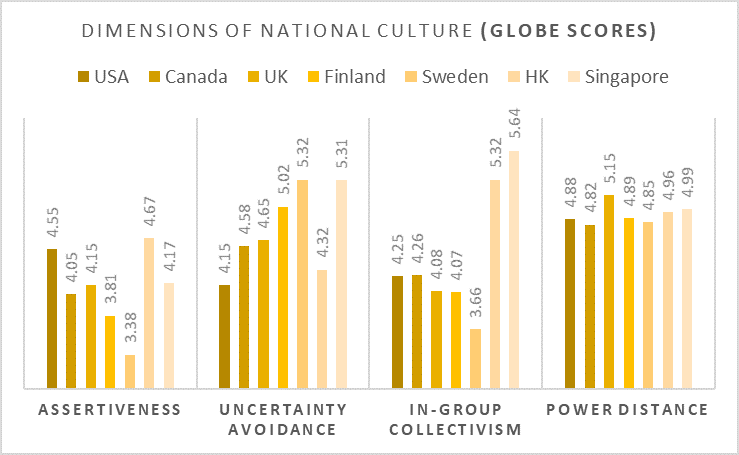

They collected data from 1,749 employees from the banking industry in seven countries (USA, Canada, UK, Finland, Sweden, Hong Kong and Singapore), and targeted four cultural dimensions that appear to be of great relevance to performance management (from the GLOBE project 2004 – a project ran by researchers from 62 countries around the world aimed at studying national cultures). These four cultural dimensions are:

- Assertiveness: the degree to which individuals tend to be dominant, even confrontational, in their relationships with others, instead of modest and tender.

- Uncertainty avoidance: the extent to which society members seek structure, rules and procedures to reduce future’s unpredictability.

- In-group collectivism: the extent to which individuals express loyalty and cohesiveness to their groups and organizations, and concern with their wellbeing.

- Power distance: the extent to which individuals accept unequal distribution of power and establish hierarchical structures that reflect tolerance for status, position, and seniority.

The seven chosen countries vary considerably across the four cultural dimensions, as shown in the graph below.

The findings of the Chiang and Birtch (2010) study offered relevant insights on the following performance management components:

- PM system’s purpose: using appraisals to train employees and plan their development for future improvement, instead of using evaluations for compensation and promotion decisions, helps clarifying expectations and reducing uncertainty of future outcomes. As such, cultures characterized by high uncertainty avoidance, low power distance and low assertiveness, like Finland and Sweden, emphasized more the developmental role of performance management.

- Formal feedback: having greater preference for open and vivid communication and the expression of one’s emotions leads to more numerous interactions and feedback occasions. For this reason, formal feedback was more frequent in cultures high on assertiveness and low on in-group collectivism and uncertainty avoidance, such as USA, UK and Canada.

- Informal feedback: communicating feedback, not only formally but also informally, was less common in high in-group collectivism cultures like Hong Kong and Singapore. They tend to avoid conflict and seek harmony, and offering feedback in general can be negatively viewed in these cultures as it may lead to potential conflict between an employee and a manager.

- Employee participation: active participation in the PM process was higher for UK and USA where employee expression is encouraged and increases perceptions of justice. In contrast, high in-group collectivist cultures, such as Singapore and Hong Kong, had the lowest level of employee participation and preferred a top-down and less transparent assessment, which is also in-line with their high power distance values.

- Rating sources: multisource feedback (including ratings from supervisor, self, customers, subordinates, team, and peers) was more prevalent in low power distance and in-group collectivist cultures, like Finland and Sweden, where employee empowerment is valued and hierarchy is less important. As such, Singapore, Hong Kong and UK tended to only rely on unidirectional evaluations from supervisors.

Organizational implications

These findings highlight the value of using culture dimensions as valuable insights to analyze and predict the effectiveness of performance management practices in a cross-border context. An important conclusion to draw is that the practices that work successfully in one country may not be appropriate in another. As such:

One could anticipate the potential resistance and challenges that may arise in different cultures and tailor practices accordingly.

Alternatively, one should introduce certain “counter-cultural” practices slowly and pay attention to how they are communicated, since PM practices (as many HR practices) can be a stimulus to organizational culture change.

In conclusion, though, organizations should have caution not to over generalize and simplify the influence of culture, as there are several other institutional, organizational and economic factors playing their important part on the effectiveness of HR practices.

——

Reference: Chiang, F. F. T., & Birtch, T. A. (2010). Appraising performance across borders: An empirical examination of the purposes and practices of performance appraisal in a multi-country context. Journal of Management Studies, 47(7), 1365–1393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00937.x