Digest 29. Transparency illusion: Are you clear enough when giving negative feedback?

Anyone who has ever been in the position of giving feedback to another person, either at the workplace or in private spheres of life, would agree that it is a very challenging task. Especially criticizing someone’s actions or performance is never easy, and yet sometimes it is necessary – for example when managers have to communicate to their employees that their performance is far from meeting expectations. To lift themselves from such uncomfortable situations, managers often end up sugarcoating their negative feedback. This means that the feedback may not be accurately communicated to the employees, jeopardizing its effectiveness.

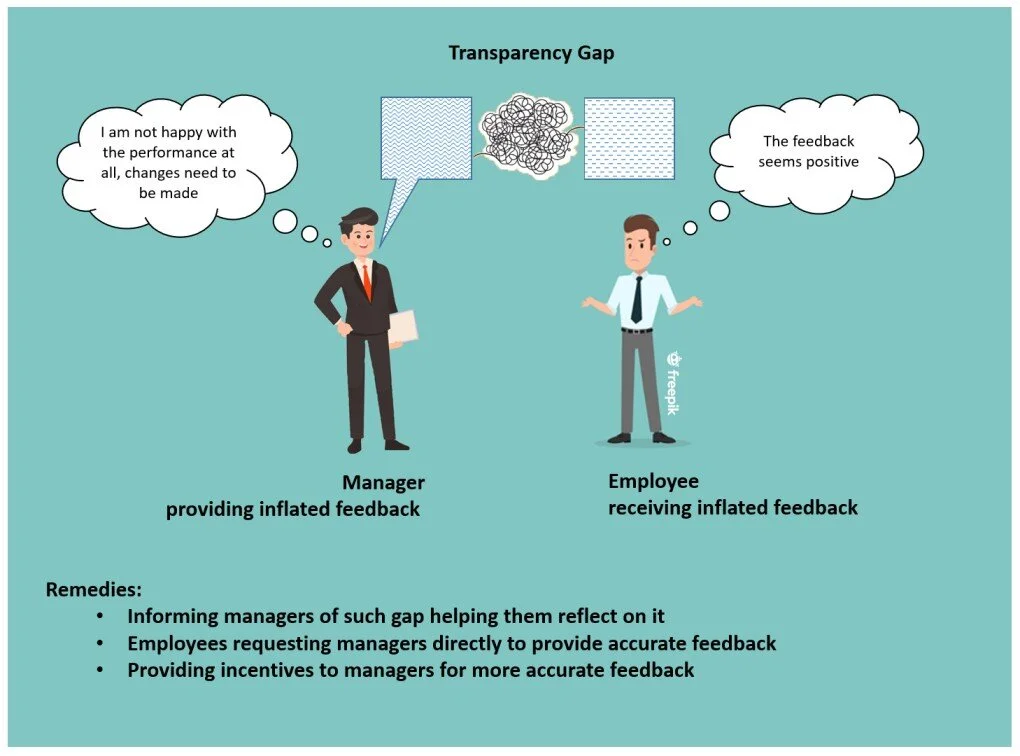

Sometimes, the reason for “inaccurate” communication of negative feedback is intentional: managers might intentionally inflate their feedback by referring to the employee’s low performance in a more positive way than it should be, to protect themselves from employee retaliation, to protect the employees from emotional harm (check out Digest 20), or to avoid negative outcomes that may follow negative feedback (check out Digest 2). But feedback inflation may also happen unintentionally – which makes it more subtle to avoid.

Why unintentional feedback inflations occur when delivering negative feedback and how to remedy?

The topic of unintentional feedback inflations has been the subject of six studies conducted by Schaerer and colleagues (2018). In the first study, data were collected from pairs of employees and their managers in a multinational organization in the educational sector, and the authors showed that managers incurred the “transparency illusion”. This is what we would call a mismatch between a manager’s anticipation of an employee’s understanding of the performance evaluation and the employee’s actual understanding of it. With this study and the subsequent one, based on role plays with over 200 students, Schaerer and colleagues also found that this transparency illusion was more frequent when managers had to deliver negative feedback in comparison to positive feedback. In further support of the transparency illusion, a third study with professionals enrolled in an MBA program showed that an external observer present to the delivery of feedback had an understanding of the performance evaluation closer to the understanding of the employees rather than the managers’.

In another set of three experiments Schaerer and his colleagues aimed to show that increasing managers’ motivation to provide accurate feedback, helps remedy the transparency illusion. In the first experiment, participants were asked to give a written feedback to their employees in a way that the recipients could “guess” the evaluation score given to them by the manager. In this experiment, some managers were warned that the evaluation might not be evident to the employees and that employees might understand the feedback in a different way. Based on this experiment, simply reminding managers about the need for accuracy helped reduce the transparency gap making the evaluation scores reported by managers and employees on average closer to one another. In a second experiment, it was shown that if managers received a message from an employee requesting accurate feedback, then the transparency gap would again be reduced, as managers’ and employees’ understanding of the evaluation would be more similar. In the third experiment, managers who were told that they would receive a monetary incentive for accurate feedback incurred less in the transparency illusion.

Overall, these studies showed that such unintentional transparency gap exists, especially in the case of delivering negative feedback, and that it is due to how the managers craft their message more than the way employees receive it. On a positive note, offering managers the opportunity to reflect on the existence of possible discrepancies reduced the transparency gap, as did the attempts at increasing either their intrinsic or extrinsic motivation to provide employees with accurate feedback.

Organizational implications

In order to reduce unintentional feedback inflation, organizations can follow these suggestions:

Informing managers that the message they try to convey in their feedback to employees might not be as evident to the employees.

Providing managers with constant reminders and continuous training on biases they might have in delivering feedback to prevent them from reverting back to bad habits.

Having a formal process of upward communication allowing the employees to express their expectations for accurate feedback prior to the session.

Developing a culture in which employees and managers can communicate openly.

Linking monetary or non-monetary incentives of managers to increase accurate feedback delivery and reduce the unintentional feedback inflation.

——

Reference: Schaerer, M., Kern, M., Berger, G., Medvec, V., & Swaab, R. I. (2018). The illusion of transparency in performance appraisals: When and why accuracy motivation explains unintentional feedback inflation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.09.002